Select Sidearea

Populate the sidearea with useful widgets. It’s simple to add images, categories, latest post, social media icon links, tag clouds, and more.

hello@youremail.com

+1234567890

+1234567890

Populate the sidearea with useful widgets. It’s simple to add images, categories, latest post, social media icon links, tag clouds, and more.

Iztok Franko

With the current COVID-19 situation, it’s just impossible not to think of the impact it will have on the airline industry. However, one thing is clear:

When demand for travel returns, airline innovation will be needed more than ever!

We all will need to change how we do business: from product and strategy to capacity planning, scheduling, revenue management and marketing.

While the extent of the changes might not be clear to you now, the speed and agility of change and innovation will be crucial.

This is why this interview and insights by Stefan Thomke couldn’t come at a better time. He is a Harvard Business School Professor and author of the book Experimentation Works: The Surprising Power of Business Experiments. Stefan is an authority on the management of innovation and has studied the best companies like Microsoft, Amazon, Booking.com, and Netflix, among others.

This is why this interview and insights by Stefan Thomke couldn’t come at a better time. He is a Harvard Business School Professor and author of the book Experimentation Works: The Surprising Power of Business Experiments. Stefan is an authority on the management of innovation and has studied the best companies like Microsoft, Amazon, Booking.com, and Netflix, among others.

Now, you’ll ask, how is business experimentation related to airline innovation?

Well, the more I listened to Stefan talk about experimentation, the more I was convinced experimentation leads to faster innovation. How?

For one, it makes your management decision-making better, more data-driven. Or as Stefan put it:

Business experimentation brings the scientific method to management decision-making. If you make changes without running experiments, you’re playing the lottery.

Ronny Kohavi, who has led experimentation at giants like Microsoft and Airbnb, shared similar data in his book, Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments:

Microsoft shared that a third of their experiments moved key metrics positively, a third moved negatively, and a third didn’t have significant impact. LinkedIn observed similar statistics.

It’s always humbling to realize that without experimentation to offer an objective true assessment, we could end up shipping both positive and negative experiments, canceling impact from each other.

Wow!

Even the giants roll out features and products that “win” only one third of the time. And they are really good. So, without experimentation, you’re playing the lottery with really poor odds.

But that is plain management. The real effect experimentation will have on your airline innovation is evident in this next quote from Stefan:

Experiments allow you to be more innovative. Experimentation gives you the courage in your innovation because it gives you the evidence to back it up.

Listen to the Diggintravel Podcast interview with Stefan via the audio player below, or read on for the full interview transcript.

And don’t forget to subscribe to the Diggintravel Podcast in your preferred podcast app to stay on top of airline innovation and digital trends!

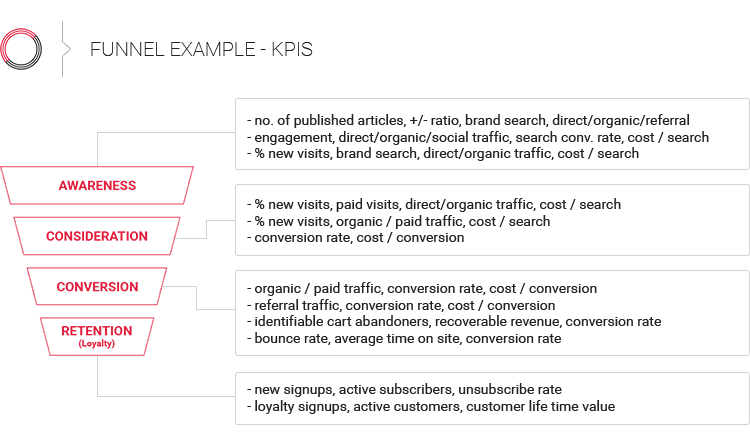

You already know that here at Diggintravel, we are all-in on conversion optimization (CRO) and experimentation. Hence, we provide you with the biggest yearly airline conversion optimization research and best airline CRO resources.

However, business experimentation is much bigger than that. When you apply it to the whole business, it can really kick-start your airline innovation. Here is Stefan’s advice for airlines:

Airlines need to realize if they want to leverage the full power of experimentation, you need to go beyond just thinking about conversions on your website. You have to start thinking about products. Can you actually experiment with the products you offer to your customers?

Iztok Franko: Hi, Stefan, and welcome to the Diggintravel Podcast.

Stefan Thomke: Thanks for having me, Franko.

Iztok: Great to have you. As I was reading your book – it’s a great book, and I encourage all the readers of Diggintravel blogs and research and our listeners of this podcast to check out Stefan’s book, Experimentation Works: The Surprising Power of Business Experiments. As I was reading your book, I was reading it from my digital lens, but the more I read your book, the more I saw it’s not about digital experimentation, where experimentation is really popular in the last couple of years; I saw a lot more about this area of experimentation. Who would you say your book is for?

Stefan: My book is for everybody. It’s not just about online. It’s also about offline brick-and-mortar. It’s not just for B2C. It’s also for B2B. Because the kinds of changes that we’re seeing in the space affect really every business, and it affects them for a number of different reasons.

First of all, we see brick-and-mortar businesses now having increasingly a digital presence, so even parts of the businesses are moving digital now, so they need to have that digital or online capability. But experimentation also works in brick-and-mortar settings. In fact, it’s been used in brick-and-mortar settings for years.

What this is really about is bringing the scientific method to management decision-making. As you know, the scientific method is all about hypotheses. It’s about experiments and so on and having that kind of mentality or that mindset in everything that a company does, all the way from the top down to the mid level to the bottom of an organization.

Iztok: One thing that also surprised me in your book is when I started thinking about experimentation in this broader sense, so not from my digital perspective, is that this field is quite an old field. If I’m not mistaken, the first or the biggest book about experimentation was written 400 years ago, right?

Stefan: We are in a very special time right now. Francis Bacon, who was a British philosopher and writer, wrote in 1620 the book Novum Organum. What does “novum organum” mean? Novum Organum was basically a book about a new instrument for building and organizing knowledge. That instrument is called the scientific method. That’s how we know it today.

He is considered to be the forefather of this method. Now, it evolved, of course, over time. Again, exactly 400 years ago. So we are in a special anniversary year, and it’s only taken us 400 years to get it into management. [laughs]

But the power of this is really interesting. Of course, compared to 400 years ago when Francis Bacon wrote about this, today we have amazing tools available. This mindset – there’s been a lot of development, of course, in the last 50 to 100 years about statistical methods. At the time, there were really no statistical methods around. But the tools that you can use to do these kinds of things are now so powerful that they’re affecting everything that they do.

I wrote my first book in 2003. That book was called Experimentation Matters, and this book was about how new technology such as modeling and simulation and all these wonderful things were changing the way R&D and product development was being done. At the time, there was really no conversion optimization and things like that around.

What has changed now is that all of these methods, the approaches that we know so well, more in a product development setting – physical products – are now entering every facet of a business. We all know about A/B testing, conversion optimization, all these kinds of things, but it’s much, much broader than that. It is really about how to run an enterprise.

Iztok: What I’m thinking right now is, for example, the two of us came into this area of experimentation from two different angles. I see a lot of these new digital people who start learning about how to optimize their websites, their online businesses, and then they touch the area of A/B testing and experimentation.

Like you said, you, on the other hand, you were analyzing the research and experimentation way before the digital world even started with this.

Stefan: I’m an engineer. [laughs]

Iztok: Yeah, me too.

Stefan: I used to do this. I started 30 years ago with this stuff in engineering. In fact, this is my other anniversary – now you can date me, how old I am – I ran my first engineering experiment – and I mean really designed experiments, not trial and error; really rigorous experiments – exactly 30 years ago, in 1990, when I was working as an engineer in a semiconductor factory.

Iztok: My background surprisingly is engineering, more like IT engineer, as well. But then I moved to marketing and I started analyzing these things. My question, Stefan, to you, is when you look at the organizations, is there a correct way to start? Because some I think start with this bottom-up approach where there is this digital guy, conversion optimization guy somewhere in the basement and he starts trying this, gets some quick wins, and then tries to spread enthusiasm to the larger commercial teams, or sometimes if they’re successful, even to the whole organization

On the other hand, I think, like you should said, your book should be for the CEOs that should look at experimentation strategically and say, “We need to start with this program. Let’s start top-down.” Which approach do you think works better, top-down or this bottom-up that I was talking initially about?

Stefan: I tell everyone who is thinking about this, just get started. If you have not started, you’d better do it, because if you don’t do this, you’re going to be at a major competitive disadvantage. In fact, in some businesses, if you don’t develop a capability quickly, you’re going to be dead.

So now, how do I get started? I think it has to happen both at the top level, but also at the middle level. You have to work it from both sides.

Here’s what organizations typically do. They start out with what I call – and the book describes it in detail and gives different examples, but it starts out with what I call a centralized organization. That is, they usually give some of that capability to a small group, maybe a digital marketing group or some sort of group within the company. They become essentially a service provider to everybody else. If you sit somewhere else in a business unit and you want to run an experiment, you have to go to them, and they’ll run the experiment for you.

Iztok: This is like a centralized experimentation team.

Stefan: Exactly. It’s a good way to get started. The problem with that, of course, is that it’s difficult to scale because that central group becomes the bottleneck. There’s really no ownership in the rest of the organization as well. Then what organizations can do is say, okay, let’s decentralize it.

The way this typically works is they will take that group, those people that know this well, and they’ll send them perhaps into different businesses and they say “Anybody in the organization can now run an experiment, and we’ll provide people that will support you, teach you what to do.” To do that, of course, you need to train people. They need to understand some basic statistics. There’s a lot of work to be done in order to get to that central form.

The issue with that, though, is you can scale it more quickly, but then it’s so distributed that often there’s no coordination between the different groups. So they may end up using different tools; they may have different rates of progress.

Iztok: And there may be some overlapping, right?

Stefan: Overlapping things, all of that. So you see all that going on, but you start losing the coordination.

Then what happens is often what they do is they move towards more of a center of excellence model. The idea of a center of excellence model is you still have a core group within an organization that owns the capability, but their job is really to advance capabilities and give some support to the different businesses who still can do these things on their own.

It’s a mixed model between centralized and decentralized, but it takes away some of the disadvantages. Of course, that requires an investment, and I think that’s where senior leaders come in. They have to rethink their roles as well in this approach. They need to understand how their own behavior, how their own leadership model affect how this is rolled out.

I see three different roles for senior leaders in this. The first role is they need to set a grand challenge that can be broken down into testable hypotheses. Their job is not to tell people which experiments to run; their job is to give them a direction so they don’t just experiment willy-nilly, like running around like chickens with heads cut off. They need to get them a sense – for example, “giving our customers the best possible online experience in the industry” or something like that, and something that can be broken down to testable hypotheses. So that’s the first.

The second is that their job is to put in place systems, resources, and the kinds of organizational designs that I just described to allow for largescale experimentation to happen.

The third one is they also need to be a role model. They have to live by the same rules as everyone else and subject their own ideas to tests. It means you cannot have an ego. You may have to walk into a meeting and display intellectual humility and not be afraid to admit it – like saying “I don’t know” or “I think I’m going to be wrong about this” and have their own things subjected to these kinds of tests.

Francis Bacon once said – again, way back then – I love this quote, by the way – “If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts. But if he will be content to begin with doubts, he shall end in certainties.” That’s what I mean.

Iztok: That’s a great quote. Going back to the three organizational models of how experimentation evolves, this is something that we see also in our airline research, where we do this yearly conversion optimization research. We have airlines who are at the beginning of the journey that need this why – why experimentation as a whole, why to start, what value it brings – and then start with the first experiment with the first team.

But lately we see more and more airlines investing in these huge digital teams. Ryanair, for example, has three digital labs around Europe. Airlines are calling themselves that they will become digital companies. For them, the challenge is to scale.

This example that you talked about, how it evolves in the decentralized model but with this guiding unit, this is what I see where the big airlines that really want to compete and be similar to Booking.com and Amazon want to achieve.

And I see in your book the example of Booking, and I also followed the work of Stuart Frisby, some of his presentations, how they scale design, and he was talking about a similar thing. They had this design principle and design function that basically was more of a teaching and a guideline for the 70+ designers that work in different decentralized teams.

Do you think this approach or this evolution is the correct one for the bigger airlines that want to follow Booking and the big players in the travel online industry?

Stefan: I think they need to follow models like Booking because if they want to own – there are many other platforms around like Booking, but if the airline wants to be more active in terms of owning the customer relationship, they need to have a testing capability. And when I say testing capability, I mean a lot of tests.

Booking runs tens of thousands of live experiments annually. That’s a huge number. I don’t know what the exact number is, but by my estimates it’s way over 30,000 a year. You can imagine the dynamics behind this. It’s an amazing force. Something like 75% of the core team of Booking, sitting around the Amsterdam area and satellites, are involved in running experiments every single day.

Trying to figure out what works and doesn’t work isn’t a guessing game anymore, because you have this amazing firepower that you can use every single day. Now, that creates a whole bunch of challenges, of course, for an organization. If you take an airline and assume that they have the infrastructure to do this, you still need an amazing number of hypotheses to be tested.

Let’s say just for the sake of argument that you could be running 10,000 experiments a year. That means that your people need to generate 10,000 hypotheses a year. Where do all these hypotheses come from? They come from people for sure, but where do these insights come from? What do these ideas come from?

What happens – and this is really interesting – is that these “digital companies” like Booking – and many others, by the way; it’s not just them – they still do all the traditional research that many non-digital companies do. They do focus groups, they do usability labs, they have psychologists on staff. They do all the kinds of things, quality research.

But what they use it for is very different. They use it for generating hypotheses that are then tested through experiments versus companies that don’t have a testing capability, and what they do is just use these insights and go directly to market. Eventually every company will run an experiment, and that is at some point they have to go to market, and they will launch something. They may not think of it as an experiment, but it is an experiment in some ways.

Iztok: If it will work or not [laughs]

Stefan: They will learn if something doesn’t work. Except at this point, it’ll be a very, very expensive lesson.

Iztok: I think you give an example of an ex-Apple guy in your book who did exactly that.

Stefan: Yeah. It’s a great story. This is a great story of how our own experience and intuitions can mislead us.

This is a guy named Ron Johnson, an Apple executive, and he was a very famous guy in the retail space because he and Steve Jobs together created the Apple Store, clearly the most successful retail concept in the last decade or so. Hugely successful.

JCPenney, a big American retailer, comes along and sees this, and they’re thinking, “Hey, if we bring Ron Johnson onboard and make him the CEO, we want him to do what he did for Apple.” So they did that and they give him a huge incentive package. He comes onboard as the CEO, and he gets started right away. He implements all the kinds of things that worked so well for Apple. They eliminate coupons, clearance racks. They fill stores with random boutiques, use technology, they eliminate cashiers, and so on and so on, all the kinds of things that you see there.

17 months later, sales had dramatically dropped at JCPenney, losses were building up, and Johnson was fired. So what happened? Well, if you listen to people on the board, one of the big problems is they didn’t test. They were in a hurry. They assumed that all the things that worked for the Apple Store would apply in a JCPenney environment, but of course, they didn’t.

I listened to a talk by Ron Johnson when he now looks back about his experience, and you know what he calls it? And by the way, he’s not an arrogant person. When you listen to him, he comes across as actually quite modest. He calls it “situational arrogance.” That is, we get so confident about our beliefs, what we think works in a particular context, that we don’t question it anymore. That’s the trap that I think a lot of managers fall into.

Iztok: I also see this on a much smaller scale in the digital world. There are a lot of articles, success studies, “This works for Booking, this works for Airbnb,” and people just copy-paste and think it should work for their business without doing the research and proper optimization and hypotheses and testing.

Stefan: Absolutely. Even Booking learned that. When they initially started to launch things on their landing pages, they took the kinds of things that worked so well in the travel industry. They figured, it works on a brochure, so why not replicate that online? Of course, when they ran it online, things didn’t work at all. What happens to work in a brochure when someone actually walks into a physical travel office doesn’t work when you actually put it into a digital experience. How do you know whether something works or not? Well, you’ve got to run the experiments.

Iztok: True. I want to come back to your thoughts before about scale. If you want to run 10,000 experiments, you need 10,000 hypotheses and things like that. I think there are different elements, and you also write them in detail in your book about how you do this at scale. We talked about we need to have capabilities, we need to have the team, the people. Then you need to have the proper organization that you talked about. We will talk a little bit later about one of the most important parts, the cultural part.

But one thing that I see also with airlines – a lot of traditional airlines are run on this legacy technology, and I see the technology and the platforms are often limiting them in how many experiments they can run because they’re just so inflexible. What I see in my research is that the best at experimentation are the ones that build their own experimentation technology, and it’s directly embedded in their booking platforms.

I saw some examples – I think it was from Microsoft and some others in your book, where they see this huge gap in experimentation when they build their own experimentation platforms. Is this correct?

Stefan: Yes. You have to look at this historically. A lot of the big players that do this at scale, like Amazon and Microsoft and Booking and even Netflix and Google and all these companies that do this at large scale, when they started out, there were really no reasonable third party solutions available, so they had no choice but to build their own platforms.

Some companies have invested an amazing amount of resources in it. If you just look at Microsoft, they have a team there of I think now 90+ people, and all they do is maintain infrastructure. A lot of companies cannot afford to have such large efforts just to build infrastructure, run infrastructure, and all that.

The good news is there are now an increasing number of third party platforms available that include some of these elements that some of these large companies have, and there are some of them around, Optimizely being one of them. That’s encouraging. That means if you want to get started – and that scares the hell out of people. They’re saying, “Oh my God, we have to now put a 50 person tech team or 20 person tech team on this.” You can just invest in a third party solution.

It is kind of interesting, because I saw the same evolution in the engineering world something like 15-20 years ago. Initially, when all these tools took off, companies built their own, but then after some time they realized that just maintaining these tools and improving them would be way too much effort, because these companies were not IT companies. They eventually moved over to third party solutions.

I think that’s going to happen in this space at some point as well. As the third party solutions are getting better and better, companies will choose that path.

Iztok: That’s definitely one of the challenges. Like you said, for the ones that want to get started, that’s a no-brainer. Select a third party tool and start running and grow with the tool as you grow with the processes, knowledge, and the scale. For the bigger ones, currently it is a bit of a challenge because if you want to do more complex experiments, this is something where the third party tools still limit you a little bit.

Stefan: They do limit you, for sure. But keep in mind, usually what I find is the real limit, the real brake is not the tool. We’ll get to this in a few minutes.

Iztok: True, true. One other thing that you mentioned before with these 10,000 experiments, 10,000 hypotheses, what you write in the book is that companies that do experimentation, you don’t see these huge wins or huge results or huge uplifts, but it’s more like it comes with quantity and a lot of small incremental wins.

But on the other hand, I also see experimentation people that would say you need to test big. Big things, big changes will bring you big results. What is your view on this?

Stefan: There are different kinds of experiments. That’s why I’m always reluctant just to call them A/B tests or conversion optimization, because I think experimentation is much bigger.

Just roughly, you can think about experiments at two different levels. At one level you have the kinds of optimization experiments that you study yourself and that you see. The idea here is to do landing pages and things, to do that conversion optimization. Typically what we do there is very small experiments, and we make very small changes. We can do that because our sample sizes are very large. And it allows us also to do cause and effect learning. We change just one variable, we randomize, and we can, with laser precision, say which of the variable changes causes what to happen. That’s one class of experiments, and many experiments are like that.

But I also see other types of experiments, which I call exploration or discovery type of experiments. There, you may change many variables at the same time. The intent there isn’t always to get precise cause and effect, because when you’re changing many variables at the same time, you can’t really pin it down on one variable.

The idea here is perhaps to maybe explore, to get some sense of directionality that allows you to say, okay, if we completely, for example, have our landing page and we make it all yellow or blue or whatever – something big – it gives us some sense of how customers are likely to respond to it. Then we can kick into optimization experiments again and then refine and fine-tune some of these things.

So I think we need to think more broadly about experimentation than just about fine-tuning and fine optimization. Having said that, though, even small experiments can have big changes in terms of revenue.

Iztok: That’s true, especially for the large airlines that have tens of millions of users on their website each month. That’s true.

Stefan: Absolutely. There’s one example in my book. Microsoft Bing, an employee ran a simple test – only took a couple days to make the software change, and much to their surprise, it ended up lifting up revenue by more than $100 million a year. Just one small change. Again, because a lot of traffic.

So the digital world, you can scale things instantly. You can expose these changes to a lot of people, and that makes it very, very powerful. I call it high velocity incrementalism, because we want to make many small changes fast, and then the cumulative impact can be huge.

Iztok: Often it’s the difference between linear and exponential growth. If you want to really grow exponentially, this is exactly what you’re talking about.

I want to touch now, in the second part of our talk, on an even more important topic for me. What I often see when we start conversion optimization – and I call it from the trenches, this bottom-up approach. We start it with digital teams, we teach them how to measure, how to do analytics, how to do user research, how to test, and then we reinforce the experimentation and we see these results. What we see what happens is you find out this – we call it first usability fails, first mistakes that are very evident because if you didn’t test and didn’t do user research, you don’t see it, and you’ll get results.

But the more you evolve this conversion optimization, the more it touches the real user problems and the closer to the product you get. This is where I see the real value of this approach when it becomes what you were writing about, the real company experimentation. Let’s say a true business process optimization or business optimization, true experimentation.

But here I think is where airlines struggle, and I wanted to pick your brains about this, because for me, airlines are like two different walls. We have these digital teams that have a lot of traffic and try to catch up with all this digital stuff and start to do experimentation, but on the other hand, the 100 year history of airline planning is like we plan one time per year, or two seasons, winter and summer. But basically all new routes, new scale, bigger scale is tested in the summer season. So basically the whole industry and the whole management has this “one time per year” experiment mindset, if I can say so.

How could we implement this experimentation where it has a much bigger impact on the routes, on the seat capacity, even on the airfare types? How do you look at this?

Stefan: A number of different thoughts on this. I’m just looking and seeing what’s happening out there, not just the airlines. Of course, there’s a lot of emphasis right now on conversion optimization, websites, and things like that.

But what’s happening now – which is really interesting because we’re going in full circles here, and this is where our mutual engineering experience actually comes in handy. I think companies are now discovering that this is so powerful on the user interfaces; why not actually use it on the products as well? Why not start using experiments at the product level, not just basically on the channel?

This is essentially where experimentation came from, where it originated. This is what I did some 15-20 years ago, even 30 years ago, when I ran my first experiments. I ran it on process and we did it on product as well. I think that’s the real power. I think airlines need to realize that if you want to leverage the full power of this, you have to go beyond just thinking about conversions on your website. You have to start thinking about products. Can you actually experiment with the products that you offer to your customers? That’s at one level.

Your second question was about the cadence, how often should we do this? We know from software development and how software development has changed in the last few years that it’s fundamentally different. In an agile approach to this, where we iterate and iterate and iterate, there’s no beginning and no end anymore. It’s a continuous process. It’s now called DevOps. I think software has recognized that the way we manage software projects is fundamentally different than the way we used to. We’re basically now continuously doing – there’s no end to this. And we have to do it fast. Again, high velocity. We have to iterate very quickly.

I think that’s the world that we’re heading towards, and I think airlines are not going to be an exception here. Maybe the mentality that they have comes from capacity planning, because they have very expensive capital equipment that they need to allocate, and perhaps that holds them back a little bit.

Iztok: I think it’s also the whole mindset. The industry is very regulated. I did an interview – and maybe we can talk about the cultural part now – I did an interview with the Head of Strategy of Eurowings Digital. Eurowings is a low-cost airline of Lufthansa in Germany, and they created a new company within the Eurowings Group, Eurowings Digital, because they said it’s just a different mindset in the digital world and experimentation, and we couldn’t get through in our main company because they were explaining about we should do MVPs and things like that, they said “nobody wants to fly on an MVP plane.” [laughs] To me, that was a great example of the different cultural part.

But I think what you’re talking about is we should still try this approach, of course in a regulated way, in a safe way, also in the airline, in the offline world, where real money is also lost or made. I think in your book you had one very good example of this offline experimentation where one company tested the opening hours of a store, if I’m not mistaken.

Stefan: Correct. Just a few thoughts, and I want to explain to you the example. I think right now, the airlines are facing a real test because of COVID-19. Things are changing every single day. Imagine you had this agile capability where you could go out and have the same flexibility and you can basically redo it, like in an agile software development approach. Just imagine how powerful that would be if you had that capability.

Going back to the examples, going beyond digital now, in more physical spaces – where this can be used as well, by the way; just the constraints are a little different – Kohl’s. Big U.S. retailer. They faced an interesting question. They did an analysis, with the help I think of some consultants, and the analysis showed that they could save millions of dollars if they opened their stores 1 hour later, and they have many, many stores in the U.S.

That calculation, that analysis can be done. It’s very easy. I think any first year MBA student can do that. You just run through the numbers and you figure out what the cost is. But that’s not the real question. The real question for the leadership, then, is not how much money they can save, but if they change the stores to opening 1 hour later, what would be the impact on revenue? Because that’s what the big unknown is. How do they know? Well, the only way to find out is to open the stores an hour later. But that could be a really expensive proposition because we don’t know, usually, how consumers behave.

So how do we do this? They ended up running disciplined experiments in a sample of their stores with a lot of rigor, with the support of software, and then basically the results told them that the effect on revenue would be very small. That then gave them the courage to be bold and make a change like this. Because if you make a change like this without running experiments, I think you’re playing the lottery here. And we remember from Ron Johnson, what he did, running it without experiments.

Experiments allow you to be more innovative. It gives you the courage to be bold in your innovation as well, because you have evidence to back you up.

Iztok: True. I see the examples with the store. I see, back from my airlines days, a lot of times we were thinking about, should we add frequency to one route, or should we change the schedule? If you could experiment or apply some of the experimentation principles – and I think some of the airlines, to be honest, do – then it’s, like you said, to make much better decisions. In the long run, it really matters.

Stefan: Absolutely.

Iztok: The funny thing with management with this COVID-19 situation – it’s really terrible for our industry, and I was really thinking it when I read your book this week and all these things were happening – it’s like experimentation happening in front of our eyes, because we have different countries with different approaches, all these different datasets. Then when people start comparing, they say, “Look, what these guys did here worked much better than what we are doing here.” I think it’s like life’s showcase for experimentation in these tough times.

Stefan: The only challenge you have right now – and that’s why you have to think it through – is you need a control. Because otherwise it’s just an observational study that means “they did this in their country and let’s do it.” But we don’t actually know whether it works in our context, just like the retail example, unless you have a control.

So when you’re facing these almost “natural” experiments here, you need to be very careful about what you learn from it, and you need to really think about what kinds of controls you could use. Sometimes there is a natural control as well when you’re thinking through it. That’s why it’s important to have people on staff who know how to do this and who know what the issues are, who know some of the analytical challenges that you face when you see these things happening around you, and they can help you then to make intelligent decisions. Again, capabilities is really what matters here.

Iztok: That’s true. Like you said, on a much smaller and less significant scale, this is what I see as one of the main challenges of experimentation. You start running the first experiment and you don’t have the capabilities in analytics, statistical capabilities, to identify control groups, sample sizes, calculate statistical significance, and things like that.

Stefan: For the airlines, it’s huge. Imagine if an airline could, through the help of experiments, maybe change their load factors by 2% or 3%. The impact is huge if you’ve got tens of thousands of flights or even more. Even small changes in load factors have a huge impact on their revenue and bottom line.

Iztok: Yeah, it’s top-down. It starts with the traffic, with acquisition costs, because a lot of traffic dissipates, so higher conversion means lower acquisition cost. And then, as you said, it reflects down to the operational things like load factor, which the impact is huge. This is I think one of the examples why Booking can invest in this, because they have proven much higher industry conversion rates, and then they can invest this back in the business.

Stefan: Absolutely.

Iztok: Stefan, maybe to end this interview, you analyze a lot of different companies, a lot of different people; what is a good profile of a person to work in experimentation? We talked, for example, about the engineering side and engineering background, which makes you naturally curious. But a lot of times I talk to people who work in experimentation and they say you need to be this entrepreneurial type, so you need to be willing to take risks, to see the bigger picture. What do you think is a good profile for a person to work in experimentation?

Stefan: That’s a really great question, and I think it ties directly back to the cultural piece again. What kinds of people do you want to have in your culture that do this sort of thing? I’ve identified seven elements in a culture, and there’s a whole chapter on culture, and it talks about people and things like that as well.

Let me give you some examples of the kinds of people that you need to do this. First of all, you need curious people, because these are the kinds of people that will see failures not as costly mistakes, but as opportunities for learning. So you need to hire for these kinds of people. You need to also cultivate them so they don’t come onboard and they’re curious, and then once they’re in an organization they’re not allowed to be curious anymore. Curiosity is really important.

One manager once told me that the way he screens for curious people in an interview is he counts the number of questions they ask him during the interview. It’s a very simple KPI, he said. [laughs] If it’s zero, then chances are they’re probably not very curious. That’s the first one.

Then the second one, I think you need people who understand that data needs to trump opinions. If in doubt, you should follow the data, even when it clashes with the opinions. We as people tend to happily accept what we call good results that confirm what our biases are, but when we get a bad result, we thoroughly investigate it. [laughs] Because we don’t seem to believe it and so forth. So people need to understand that.

Now, that doesn’t mean that there is no room for opinions. Of course opinions and intuition, all these things are important to write down a hypothesis. But when it comes to making decisions and results, we need to make sure that we do really understand the data. Again, it doesn’t mean that we blindly follow the data; there may be strategic reasons why we don’t do things. But let’s please look at the data and understand the power of the data.

I think a third example – and there are many more of these things – I think we need people who are ethically sensitive, because when you’re running experiments, you also have an ethical responsibility. You should never run experiments that harm people. Sometimes it’s not so clear-cut what’s ethical and what’s not ethical, so you need to create an environment where people discuss this and they challenge each other about the ethics of what they’re trying to do.

And when you get it wrong, the backlash can be severe, as we learned in Facebook and other companies. So having someone who has ethical sensitivity and also cultivating that ethical sensitivity I think is key in an organization.

That would be just a few examples. There’s a lot more to this, of course. Again, it’s Chapter 4 in the book. I welcome anybody who has any questions. But there’s a lot in the book about how to do this and what kind of organization you need, many examples, what kind of transformation you have to go through, and so forth.

Iztok: Thank you, Stefan. These were great examples, and also I think great insights for all of us. As I said, I think it’s crucial that all businesses, also airlines – not only airlines, but everybody else – realize that experimentation and this scientific approach to growth is the right one.

I encourage, as I did at the beginning, everybody, all the listeners, all my readers, to learn more about you, about the book. Find the book on Amazon. Leave a 5-star review once you read it. I did today. For me, as I said, as a huge enthusiast in this field, I was really pleasantly surprised when I finished it because I learned a lot of new things.

Stefan: Thank you very much, Franko. Very generous of you.

Iztok: Tell me at the end, Stefan, apart from the book, where else can people learn more about you?

Stefan: Of course, if they want to learn about my work, the easy way is always to come to my webpage at Harvard Business School. The way to find it is either you go HBS and then my last name, Thomke, and you’ll end up on my page at the school. You can also use www.thomke.com. That will take you to my Harvard Business School webpage as well.

On there, I list all my publications. I write about this stuff all the time. I have many articles on this as well, case studies, and things like that. They can also email me. It’s just t@hbs.edu. They can send a connect request on LinkedIn. But what I do ask people is to send a message along with it just to tell me where they heard me so I make a connection, since I get a lot of requests from people that I don’t know. I want them to see where we met. I’d like to have people in my network that have actually met me, either virtually met me or physically met me.

Iztok: I would say that should be a common courtesy, although on LinkedIn it’s just not. [laughs] It’s great advice for how to reach out to great and smart people like you. I will include all the links that you mentioned in the podcast notes and also in the article that will support this chat, so I’ll make sure that everybody will be able to find you, Stefan.

Stefan: Thank you so much, Franko.

Iztok: Thank you again for the chat. A lot of fun with experimentation going forward.

Stefan: Thank you. [laughs] Thank you so much.

I am passionate about digital marketing and ecommerce, with more than 10 years of experience as a CMO and CIO in travel and multinational companies. I work as a strategic digital marketing and ecommerce consultant for global online travel brands. Constant learning is my main motivation, and this is why I launched Diggintravel.com, a content platform for travel digital marketers to obtain and share knowledge. If you want to learn or work with me check our Academy (learning with me) and Services (working with me) pages in the main menu of our website.

Download PDF with insights from 55 airline surveyed airlines.

Thanks! You will receive email with the PDF link shortly. If you are a Gmail user please check Promotions tab if email is not delivered to your Primary.

Seems like something went wrong. Please, try again or contact us.

No Comments